Behind the bookshelves: The life of a heritage consultant

Heritage Consultancy is a small but integral part of Purcell. Our tool is focused research but the skill, and the challenge, lies in its practical application and presentation. The research cannot be self-indulgent in any way: unlike a university dissertation, relishing in a tangent is a rare luxury. This can be frustrating but all the more fulfilling as this targeted research forms and fuels part of a much larger process. It provides a pivotal point of departure for heritage advice, architectural proposals and conservation recommendations.

Research does not adopt a typical procedure; each building requires a tailored research approach in order to unearth its story. Whilst some buildings reveal armfuls of relevant archives, many have sparse sources and require more physical analysis onsite. Memories and anecdotes of locals, workers or residents can also supplement our understanding. This direct and indirect study of buildings allows us to thread together a historical narrative and mark up historic development plans, which in turn aid a thorough understanding of the building’s significance, as well as informing and guiding proposals.

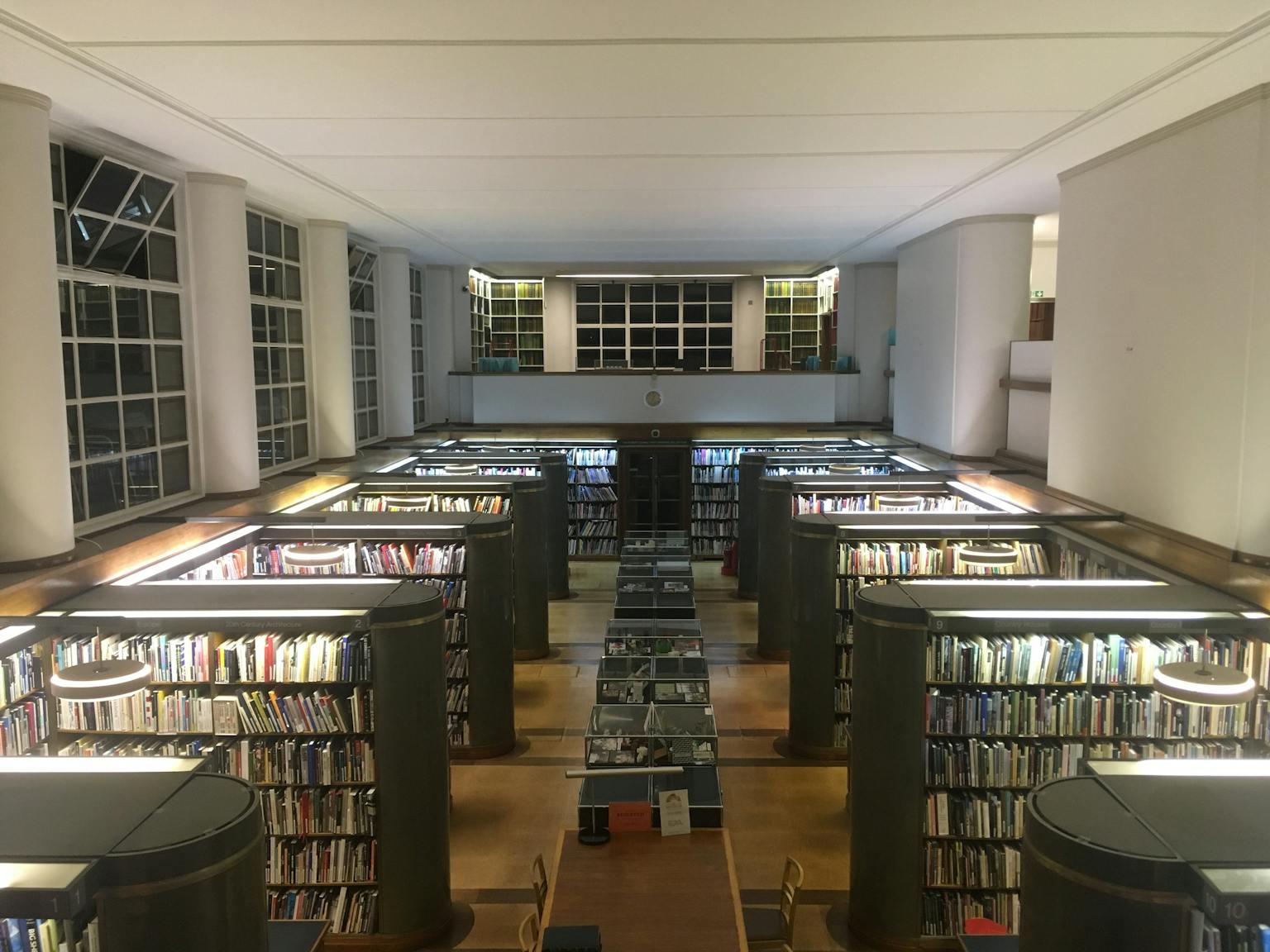

Archival research is the first port-of-call. The primary aim is to dig up original or historical plans to inform our understanding of how a building has developed. There is nothing so simple as a universal catalogue for archives, nationally and locally. This would be too easy.

Perhaps it is best to think about different depths of archival research. The shallowest and broadest platform is the National Archives at Kew where material of national importance is housed. Or even guarded: woe betide the unlucky researcher who tries to sneak a rubber-tipped pencil into the reading rooms of this bastion. Here, once you’ve passed through customs, you might find plans relevant to buildings such as the Institute of Mechanical Engineers or the National Portrait Gallery.

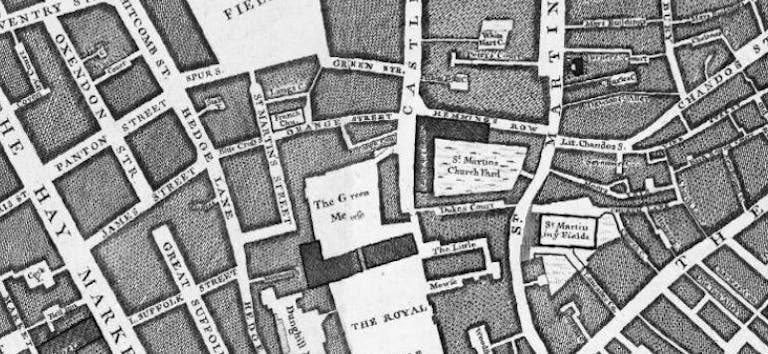

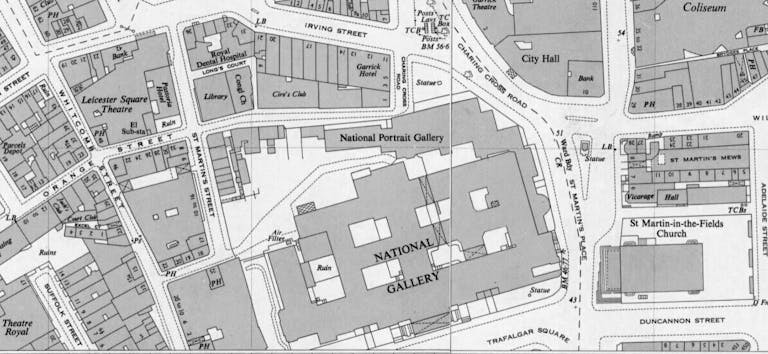

These maps, sourced online, show the development of the National Portrait Gallery site: John Rocque’s map of London, dating to 1746, and three Ordnance Survey maps (1868-73, 1895, 1951). In the mid-eighteenth century, before the Gallery was built, the site was occupied by a church yard and workhouse, with the Royal Mews in close proximity; by the late nineteenth century the National Portrait Gallery had been built immediately to the east of the National Gallery. The Gallery’s L-shaped plan reflects the constraints of the site owing to the slim wedge of land available.

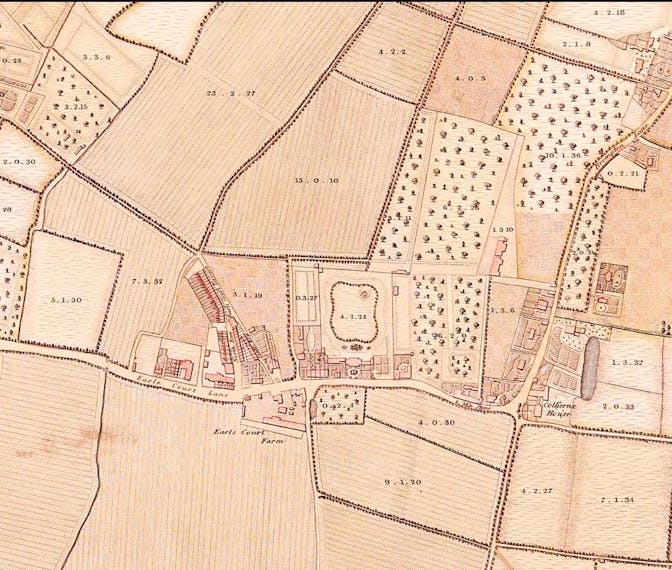

Whilst the National Archives might not house specific building plans of listed (but not nationally important) terraced houses in say, Kensington, the local authority library, in this case Kensington and Chelsea Local Studies, may well hold drainage plans and local maps showing the site. Thomas Starling’s 1822 map provides an insight into the early history of the area, before the patchwork of fields, containing little other than a sleepy Earl’s Court Farm, was developed.

Local archives, although less broad in scope, often allow deeper research on a specific site; they might for example hold historical photos dating back to the late nineteenth century. Beyond London, the equivalent is the County Record Offices, where early maps of surrounding countryside, historical OS maps and, if you’re lucky, plans may allow you to hone in on the historical development of the site and its environs. Norfolk Record Office for example, produced numerous historic maps (medieval, tithe, OS), as well as detailed histories and archival photographs of small Norfolk villages such as Cley, Blakeney and Wiveton, which proved pivotal for the North Norfolk Conservation Area Appraisals.

Many libraries fail to yield the information you think you want at the time (often owing to time constraints). However, it is weirdly exhilarating when you happen upon something unexpected, whether useful or merely a bizarre oddity. Accidentally unearthing the gnarled fingernail of John Flamsteed, the First Astronomer Royal, neatly packaged in the Cambridge University Library was an example of the latter. Some digressions are unavoidable. Although the research on the Royal Observatory at Greenwich did not benefit from this grimy find, it did make the project more vivid. Dead ends are common but lateral thinking can sometimes facilitate a bypass. A simple example being The Victorian Holiday Inn at Farnborough, on which the Hampshire Record Office was not relinquishing much information. Upon studying old maps and learning its former name was ‘The Queen’s Hotel’, the flood barriers opened and endless deeds and plans materialised.

Physical analysis of a building is a prerequisite for most reports; however, where there is little archival material, fabric analysis comes into its own, allowing professional speculation on the dating of fabric. A current project at Kensington High Street involves the refurbishment of a block of shop fronts with the intention to restore lost historical features and character to the front elevation. There was no sign of plans or elevations of the original Edwardian shop fronts; instead, a thorough analysis of surviving nineteenth century shop front features along the High Street proved invaluable. At first glance it seemed very little remained in the way of historical features, although, upon focused inspection, isolated fragments forming visual reminders of the former shop fronts began to reveal themselves.

These features included multi-paned windows, fascia boards, pilasters, consoles and capitals, canopies and stall risers, although these elements rarely co-existed in one shop front. The survey showed that the survival of historical shop fronts was more common on the streets adjoining the busy high street, possibly as these quieter backwaters were less affected by the need for development. These streets contain exemplar Edwardian shop windows, with multiple transom lights or rounded upper sections, as well as recessed doors and tiled entrance lobbies. Close observation, revealing valuable Victorian and Edwardian precedents, helped mitigate the lack of specific historical plans and elevations.

At an entirely different setting, at a private estate in Warwickshire, a Capability Brown-crafted landscape in Warwickshire, first-hand exploration of the grounds was equally essential, this time in order to advise on the possible location of a new house. The seventeenth century house was demolished following the Second World War, although the landscape bears remnants of several stages of landscape design. The orientation of the original stables and ancillary buildings, lay-out of the Victorian terracing, position of the serpentine lake and placing of the grand gates and drives led to the judgement that the house should sit central to the composition, where the original house lay.

Detective work on site can have its perils, whether momentarily lost in the basement of a labyrinthine cruciform-planned building and struggling to find the light of day or, upon closely examining historic wall fabric, being mistaken for a rat trapper or skirting board fanatic rather than a heritage sleuth. Whether venturing in to photograph men’s WCs, or bent double recording nineteenth century drain details, you can run the risk of some alarmed of accusatory looks, or even yells of ‘get a life’. A crucial lesson learnt was never wear a skirt on a construction site, let alone a floor-length orange one, paired with the obligatory high-vis jacket, you will resemble a ridiculous double-ended highlighter.

Heritage Consultancy is versatile and constantly takes on fresh dimensions; at the Ram Brewery in Wandsworth we worked, for the first time, with the architects as co-curators on a cultural strategy linking the brewery with the wider Wandsworth area. Faced with a large stable building bursting with intriguing brewery artefacts, we sorted, sifted and carefully selected the objects to be exhibited. These artefacts, alongside our interpretation and the architects’ display, spell out the story of the Ram Brewery, for example a plaque memorialising the Surrey Iron Railway, which served the brewery (the first ever public railway), a Cooper’s incomplete wooden casks, a malted barley sampler and a 1960s four-in-hand tin (known as ‘party can’). Interaction with John Hatch, a former Young’s employee and now site manager, was invaluable. John has brewed a weekly barrel of beer since the Brewery site closed; his knowledge and memories undoubtedly coloured and enlivened the project.

Direct discussion was also a key factor for the Historic Building Record (HBR) on the National Institute of Medical Research (NIMR) at Mill Hill where we carried out Oral History interviews with two former employees, the librarian and the lab assistant to Frank Hawking (father of Stephen Hawking). Alongside the textual and visual facets of the HBR, the interviews not only filled in gaps relating to the layout of the site, but also provided a more human insight into life at the Institute with amusing anecdotes and observations. The find of a dusty pile of plans in a forgotten corner of the NIMR proved to be a goldmine. Following futile pursuit of original material in various national and local archives, these plans, never before recorded or catalogued, included the architect Maxwell Ayrton’s original plans for the main, cruciform building.

Despite the dead ends and false trails, it is always possible to enhance our knowledge through research, whether archival, physical or oral. Such knowledge, presented appropriately, can form the backbone for proposals and plans. To play a part in the future life of a building in this way is enormously rewarding and fulfilling.